This report on the history of the Ku Klux Klan, America’s first terrorist organization, was prepared by the Klanwatch Project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. Klanwatch was formed in 1981 to help curb Klan and racist violence through litigation, education and monitoring.

This report on the history of the Ku Klux Klan, America’s first terrorist organization, was prepared by the Klanwatch Project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. Klanwatch was formed in 1981 to help curb Klan and racist violence through litigation, education and monitoring.

This is a history of hate in America — not the natural discord that characterizes a democracy, but the wild, irrational, killing hate that has led men and women throughout our history to extremes of violence against others simply because of their race, nationality, religion or lifestyle.

Since 1865, the Ku Klux Klan has provided a vehicle for this kind of hatred in America, and its members have been responsible for atrocities that are difficult for most people to even imagine. Today, while the traditional Klan has declined, there are many other groups which go by a variety of names and symbols and are at least as dangerous as the KKK.

Some of them are teenagers who shave their heads and wear swastika tattoos and call themselves Skinheads; some of them are young men who wear camouflage fatigues and practice guerrilla warfare tactics; some of them are conservatively dressed professionals who publish journals filled with their bizarre beliefs — ideas which range from denying that the Nazi Holocaust ever happened to the contention that the U.S. federal government is an illegal body and that all governing power should rest with county sheriffs.

Despite their peculiarities, they all share the deep-seated hatred and resentment that has given life to the Klan and terrorized minorities and Jews in this country for more than a century.

The Klan itself has had three periods of significant strength in American history — in the late 19th century, in the 1920s, and during the 1950s and early 1960s when the civil rights movement was at its height. The Klan had resurgence again in the 1970s, but did not reach its past level of influence. Since then, the Klan has become just one element in a much broader spectrum of white supremacist activity.

It’s important to understand, however, that violent prejudice is not limited to the Ku Klux Klan or any other white supremacist organization. Every year, murders, arsons, bombings and assaults are committed by people who have no ties to an organized group, but who share their extreme hatred. I learned the importance of history at an early age — my father, the late Horace Mann Bond, taught at several black colleges and universities. He showed me that knowing the past is critical to making sense of the present. The historical essays in this magazine explain the roots of racism and prejudice which sustain the Ku Klux Klan.

As a young civil rights activist working alongside John Lewis, Andrew Young, the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and many others, I saw the Ku Klux Klan as an all-too visible power in many of the places we went to organize voter registration and protest segregation.

We knew what the Klan was, and often we had a pretty good idea of who its members were. We also knew what Klansmen would do to us if they could get away with it.

For many years the KKK quite literally could get away with murder. The Ku Klux Klan was an instrument of fear, and black people, Jews and even white civil rights workers knew that the fear was intended to control us, to keep things as they had been in the South through slavery, and after that ended, through Jim Crow. This fear of the Klan was very real because, for a long time, the Klan had the power of Southern society on its side.

But in time that changed. It is a tribute to our laws that the Klan gradually was unmasked and its illegal activities checked.

Now, of course, I turn on my television set and see people in Klan robes or military uniforms again handing out hate literature on the town square. I read in my newspaper of crosses again burned in folks’ yards, and it seems as if we are back in the Sixties.

Some say the Klan today should just be ignored. Frankly, I’d like to do that. I’m tired of wasting my time on the KKK. I have better things to do.

But history won’t let me ignore current events. Those who would use violence to deny others their rights can’t be ignored. The law must be exercised to stay strong. And even racists can learn to respect the law.

That’s why this special report was prepared — to show the background of the KKK and its battle with the law, and to point out the current reasons why hate groups can’t be ignored. This hate society was America’s first terrorist organization. As we prepare for the 21st century, we need to prepare for the continued presence of the Klan. Unfortunately, malice and bigotry aren’t limited by dates on a calendar.

This report was produced by the Southern Poverty Law center’s Klanwatch Project. The SPLC is a private, nonprofit, public interest organization located in Montgomery, Alabama. It established Klanwatch in 1981 to monitor white supremacist activities throughout the United States. Together, SPLC attorneys and Klanwatch investigators have won a number of major legal battles against Klan members for crimes they committed.

This is not a pretty part of American history — some of the things you read here will make you angry or ashamed; some will turn your stomach. But it is important that we try to understand the villains as well as the heroes in our midst, if we are to continue building a nation where equality and democracy are preserved.

The bare facts about the birth of the Ku Klux Klan and its revival half a century later are baffling to most people today. Little more than a year after it was founded, the secret society thundered across the war-torn South, sabotaging Reconstruction governments and imposing a reign of terror and violence that lasted three or four years. And then as rapidly as it had spread, the Klan faded into the history books. After World War I, a new version of the Klan sputtered to life and within a few years brought many parts of the nation under its paralyzing grip of racism and bloodshed. Then, having grown to be a major force for the second time, the Klan again receded into the background. This time it never quite disappeared, but it never again commanded such widespread support.

Today, it seems incredible that an organization so violent, so opposed to the American principles of justice and equality, could twice in the nation’s history have held such power. How did the Ku Klux Klan — one of the nation’s first terrorist groups — so instantly seize the South in the aftermath of the Civil War? Why did it so quickly vanish? How could it have risen so rapidly to power in the 1920s and then so rapidly have lost that power? And why is this ghost of the Civil War still haunting America today with hatred, violence and sometimes death for its enemies and its own members?

The answers do not lie on the surface of American history. They are deeper than the events of the turbulent 1960s, the parades and cross burnings and lynching’s of the 1920s, beyond even the Reconstruction era and the Civil War. The story begins, really, on the frontier, where successive generations of Americans learned hard lessons about survival. Those lessons produced some of the qualities of life for which the nation is most admired — fierce individualism, enterprising inventiveness, and the freedom to be whatever a person wants and to go wherever a new road leads.

But the frontier spirit included other traits as well, and one was a stubborn insistence on the prerogative of “frontier justice” — an instant, private, very personal and often violent method of settling differences without involving lawyers or courts. As the frontier was tamed and churches, schools and courthouses replaced log trading posts, settlers substituted law and order for the older brand of private justice. But there were always those who did not accept the change. The quest for personal justice or revenge became a key motivation for many who later rode with the Ku Klux Klan, especially among those who were poor and uneducated.

A more obvious explanation of the South’s widespread acceptance of the Klan is found in the institution of slavery. Freedom for slaves represented for many white Southerners a bitter defeat — a defeat not only of their armies in the field but of their economic and social way of life. It was an age old nightmare come true, for early in Southern life whites in general and plantation owners in particular had begun to view the large number of slaves living among them as a potential threat to their property and their lives.

A series of bloody slave revolts in Virginia and other parts of the South resulted in the widespread practice of authorized night patrols composed of white men specially deputized for that purpose. White Southerners looked upon these night patrols as a civic duty, something akin to serving on a jury or in the militia. The mounted patrols, or regulators, as they were called, prowled Southern roads, enforcing the curfew for slaves, looking for runaways, and guarding rural areas against the threat of black uprisings. They were authorized by law to give a specific number of lashes to any violators they caught. The memory of these legal night riders and their whips was still fresh in the minds of both defeated Southerners and liberated blacks when the first Klansmen took to those same roads in 1866.

An even more immediate impetus for the Ku Klux Klan was the civil War itself and the reconstruction that followed. When robed Klansmen were at their peak of power, alarmed Northerners justifiably saw in the Klan an attempt of unrepentant confederates to win through terrorism what they had been unable to win on the battlefield. Such a simple view did not totally explain the Klan’s sway over the South, but there is little doubt that many a confederate veteran exchanged his rebel gray for the hoods and sheets of the Invisible Empire.

Finally, and most importantly, there were the conditions Southerners were faced with immediately after the war. Their cities, plantations and farms were ruined; they were impoverished and often hungry; there was an occupation army in their midst; and Reconstruction governments threatened to usurp the traditional white ruling authority. In the first few months after the fighting ended, white Southerners had to contend with the losses of life, property and, in their eyes, honor. The time was ripe for the Ku Klux Klan to ride.

Robert R. Lee’s surrender was not fully nine months past when six young ex-confederates met in a law office in December 1865 to form a secret club that they called the Ku Klux Klan. From that beginning in the little town of Pulaski, Tennessee, their club began to grow. Historians disagree on the intention of the six founders, but it is known that word quickly spread about a new organization whose members met in secret and rode with their faces hidden, who practiced elaborate rituals and initiation ceremonies.

Much of the Klan’s early reputation may have been based on almost frivolous mischief and tomfoolery. At first, a favorite Klan tactic had been for a white-sheeted Klansman wearing a ghoulish mask to ride up to a black family’s home at night and demand water. When the well bucket was offered, the Klansman would gulp it down and demand more, having actually poured the water through a rubber tube that flowed into a leather bottle concealed beneath his robe. After draining several buckets, the rider would exclaim that he had not had a drink since he died on the battlefield at Shiloh. He then galloped into the night, leaving the impression that ghosts of confederate dead were riding the countryside.

The presence of armed white men roving the countryside at night reminded many blacks of the pre-war slave patrols. The fact that Klansmen rode with their faces covered intensified blacks’ suspicion and fear. In time, the mischief turned to violence. Whippings were used first, but within months there were bloody clashes between Klansmen and blacks, Northerners who had come South, or Southern unionists. from the start, however, there was also a sinister side to the Klan.

By the time the six Klan founders met in December 1865, the opening phase of reconstruction was nearly complete. All 11 of the former rebel states had been rebuilt on astonishingly lenient terms which allowed many of the ex-confederate leaders to return to positions of power. Southern state legislatures began enacting laws that made it clear that the aristocrats who ran them intended to yield none of their pre-war power and dominance over poor whites and especially over blacks. These laws became known as the Black codes and in some cases amounted to a virtual re-enslavement of blacks.

In Louisiana, the Democratic convention resolved that “we hold this to be a Government of White People, made and to be perpetuated for the exclusive benefit of the White race, and . that the people of African descent cannot be considered as citizens of the United States.” Mississippi and Florida, in particular, enacted vicious Black codes, other Southern states (except North Carolina) passed somewhat less severe versions, and President Andrew Johnson did nothing to prevent them from being enforced.

These laws and the hostility and violence that erupted against blacks and Union supporters in the South outraged Northerners who just a few months before had celebrated victory, not only over the Confederacy but its system of slavery as well. In protest of the defiant Black Codes, Congress refused to seat the new Southern senators and representatives when it reconvened in December 1865 after a long recess. At the moment the fledgling Klan was born in Pulaski, the stage was set for a showdown between Northerners determined not to be cheated out of the fruits of their victory and die-hard Southerners who refused to give up their supremacy over blacks.

Ironically, the increasingly violent activities of the Klan throughout 1866 helped prove the argument of Radical Republicans in the North, who wanted harsher measures taken against Southern governments as part of their program to force equal treatment for blacks. Partly as a result of news reports of Klan violence in the South, the radicals won overwhelming victories in the congressional elections of 1866. In early 1867, they made a fresh start at Reconstruction. In March 1867, congress overrode President Johnson’s veto and passed the Reconstruction Acts, which abolished the ex-confederate state governments and divided 10 of the 11 former rebel states into military districts. The military governors of these districts were charged with enrolling black voters and holding elections for new constitutional conventions in each of the 10 states, which led to the creation of the radical Reconstruction Southern governments.

In April 1867, a call went out for all known Ku Klux Klan chapters or dens to send representatives to Nashville, Tenn., for a meeting that would plan, among other things, the Klan response to the new Federal Reconstruction policy.

Throughout the summer and fall, the Klan had steadily become more violent. Thousands of the white citizens of west Tennessee, northern Alabama and part of Georgia and Mississippi had by this time joined the Klan. Many now viewed the escalating violence with growing alarm — not necessarily because they had sympathy for the victims, but because the night riding was getting out of their control. Anyone could put on a sheet and a mask and ride into the night to commit assault, robbery, rape, arson or murder. The Klan was increasingly used as a cover for common crime or for personal revenge.

The Nashville Klan convention was called to grapple with these problems by creating a chain of command and deciding just what sort of organization the Klan would be. The meeting gave birth to the official philosophy of white supremacy as the fundamental creed of the Ku Klux Klan. Throughout the summer of 1867 the Invisible Empire changed, shedding the antics that had brought laughter during its parades and other public appearances, and instead taking on the full nature of a secret and powerful force with a sinister purpose.

All the now-familiar tactics of the Klan date from this period — the threats delivered to blacks, radicals and other enemies warning them to leave town; the night raids on individuals they singled out for rougher treatment; and the mass demonstrations of masked and robed Klansmen designed to cast their long shadow of fear over a troubled community.

By early 1868, stories about Klan activities were appearing in newspapers nationwide, and reconstruction governors realized they faced nothing less than an insurrection by a terrorist organization. Orders went out from state capitols and Union army headquarters during the early months of 1868 to suppress the Klan.

But it was too late. From middle Tennessee, the Klan quickly was established in nearby counties and then in North and South Carolina. In some counties the Klan became the de facto law, an invisible government that state officials could not control.

When Tennessee Governor William G. Brownlow attempted to plant spies within the Klan, he found the organization knew as much about his efforts as he did. One Brownlow spy who tried to join the Klan was found strung up in a tree, his feet just barely touching the ground. Later another spy was stripped and mutilated, and a third was stuffed in a barrel in Nashville and rolled down a wharf and into the Cumberland River, where he drowned.

With the tacit sympathy and support of most white citizens often behind it, the Klan worked behind a veil that was impossible for Brownlow and other Reconstruction governors to pierce. But even though a large majority of white Southerners opposed the Radical state governments, not all of them approved of the hooded order’s brand of vigilante justice. During its first year, the Klan’s public marches and parades were sometimes hooted and jeered at by townspeople who looked upon them as a joke. Later, when the Klan began to use guns and whips to make its point, some white newspaper editors, ministers and other civic leaders spoke out against the violence.

But in the late 1860s, white Southern voices against the Klan were in the minority. One of the Klan’s greatest strengths during this period was the large number of editors, ministers, former Confederate officers and political leaders who hid behind its sheets and guided its actions. Among them, none was more widely respected in the South than the Klan’s reputed leader, General Nathan Bedford Forrest, a legendary Confederate cavalry officer who settled in Tennessee and apparently joined the Klan fairly soon after it began to make a name for itself. Forrest became the Klan’s first imperial wizard, and in 1867 and 1868 there is little doubt that he was its chief missionary, traveling over the South, establishing new chapters and quietly advising its new members.

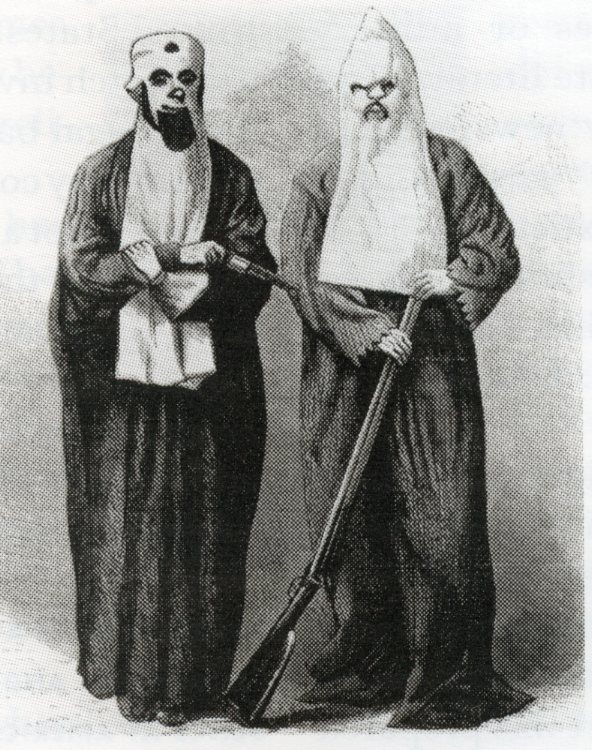

The ugly side of the Ku Klux Klan, the mutilations and floggings, lynching’s and shootings, began to spread across the South in 1868, and any words of caution that may have been expressed at the Nashville meeting were submerged beneath a stream of bloody deeds.

As the violence escalated, it turned to general lawlessness, and some Klan groups even began fighting each other. In Nashville, a gang of outlaws who adopted the Klan disguise came to be known as the Black Ku Klux Klan. For several months middle Tennessee was plagued by a guerrilla war between the real and bogus Klan’s.

The Klan was also coming under increased attack by Congress and the Reconstruction state governments. The leaders of the Klan thus realized that the order’s end was at hand, at least as any sort of organized force to serve their interests. It is widely believed that Forrest ordered the Klan disbanded in January 1869, but the surviving document is rather ambiguous. (Some historians think Forrest’s “order” was just a trick so he could deny responsibility or knowledge of Klan atrocities.)

Whatever the actual date, it is clear that as an organized, cohesive body across the South, the Ku Klux Klan had ceased to exist by the end of 1869.

That did not end the violence, however, and as atrocities became more widespread, Radical legislatures throughout the region began to pass very restrictive laws, impose martial law in some Klan dominated counties, and actively hunt Klan leaders. In 1871, Congress held hearings on the Klan and passed a harsh anti-Klan law modeled after a North Carolina statute. Under the new federal law, Southerners lost their jurisdiction over the crimes of assault, robbery and murder, and the president was authorized to declare martial law and suspend the writ of habeas corpus. Night riding and the wearing of masks were expressly prohibited. Hundreds of Klansmen were arrested, but few actually went to prison.

The laws probably dampened the enthusiasm for the Ku Klux Klan, but they can hardly be credited with destroying the hooded order. By the mid-1870s, white Southerners didn’t need the Klan as much as before because they had by that time retaken control of most Southern state governments. Klan terror had proven very effective at keeping black voters away from the polls. Some black officeholders were hanged and many more were brutally beaten. White Southern Democrats won elections easily and then passed laws taking away the rights blacks had won during Reconstruction.

The result was an official system of segregation which was the law of the land for more than 80 years. This system was called “separate but equal,” which was half true — everything was separate, but nothing was equal.

During the last half of the 19th century, memories of the Ku Klux Klan’s brief grip on the South faded, and its bloody deeds were forgotten by many whites who were once in sympathy with its cause. On the national scene, two events served to set the stage for the Ku Klux Klan to be reborn early in the 20th century.

The first was massive immigration, bringing some 23 million people from Great Britain, Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Russia and a great cry of opposition from some Americans. The American Protective Association, organized in 1887, reflected the attitude of many Americans who believed that the nation was being swamped by alien people. This organization, a secret, oath bound group, was especially strong in the Middle West, where the reborn Ku Klux Klan would later draw much of its strength.

The other major event which prepared the ground for the Klan’s return was World War I, which had a wrenching, unsettling effect on the nation. On the European battlefields, white Americans again were exposed to unrestrained bloodshed while blacks served in the uniform of their country and saw open up before them a new world. Back at home, Americans learned suspicion, hatred and distrust of anything alien, a sentiment which led to the rejection of President Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations.

In the South, yet another series of events occurred which helped breathe life into the Klan several decades later. In the 1890s, an agrarian Populist movement tried to build a coalition of blacks and poor whites against the mill owners, large landholders and conservative elite of the Old South. The aristocracy responded with the old cry of white supremacy and the manipulation of black votes. As a result, the Populists were substantially turned back in every Deep South state except Georgia and North Carolina. A feeling spread across the South, shared by both the aristocracy and many poor whites, that blacks had to be frozen out of society.

The 1890s marked the beginning of efforts in the Deep South to deny political, social and economic power to blacks. Most segregation and disenfranchisement laws date from that period. It was also the beginning of a series of lynching of blacks by white mobs. The combination of legalized racism and the constant threat of violence eventually led to a major black migration to Northern cities.

The origin of the Ku Klux Klan was a carefully guarded secret for years, although there were many theories to explain its beginnings. One popular notion held that the Ku Klux Klan was originally a secret order of Chinese opium smugglers. Another claimed it was begun by Confederate prisoners during the war. The most ridiculous theory attributed the name to some ancient Jewish document referring to the Hebrews enslaved by the Egyptian pharaohs.

In fact, the beginning of the Klan involved nothing so sinister, subversive or ancient as the theories supposed. It was the boredom of small-town life that led six young Confederate veterans to gather around a fireplace one December evening in 1865 and form a social club. The place was Pulaski, Tenn., near the Alabama border. When they reassembled a week later, the six young men were full of ideas for their new society. It would be secret, to heighten the amusement of the thing, and the titles for the various offices were to have names as preposterous-sounding as possible, partly for the fun of it and partly to avoid any military or political implications.

Thus the head of the group was called the Grand Cyclops. His assistant was the Grand Magi. There was to be a Grand Turk to greet all candidates for admission, a Grand Scribe to act as secretary, night hawks for messengers and a Lictor to be the guard. The members, when the six young men found some to join, would be called Ghouls. But what to name the society itself?

The founders were determined to come up with something unusual and mysterious. Being well-educated, they turned to the Greek language. After tossing around a number of ideas, Richard R. Reed suggested the word “kuklos,” from which the English words “circle” and “cycle” are derived. Another member, Capt. John B. Kennedy, had an ear for alliteration and added the word “”clan.” after tinkering with the sound for a while they settled on Ku Klux Klan. The selection of the name, chance though it was, had a great deal to do with the Klan’s early success. Something about the sound aroused curiosity and gave the fledgling club an immediate air of mystery, as did the initials K.K.K., which were soon to take on such terrifying significance.

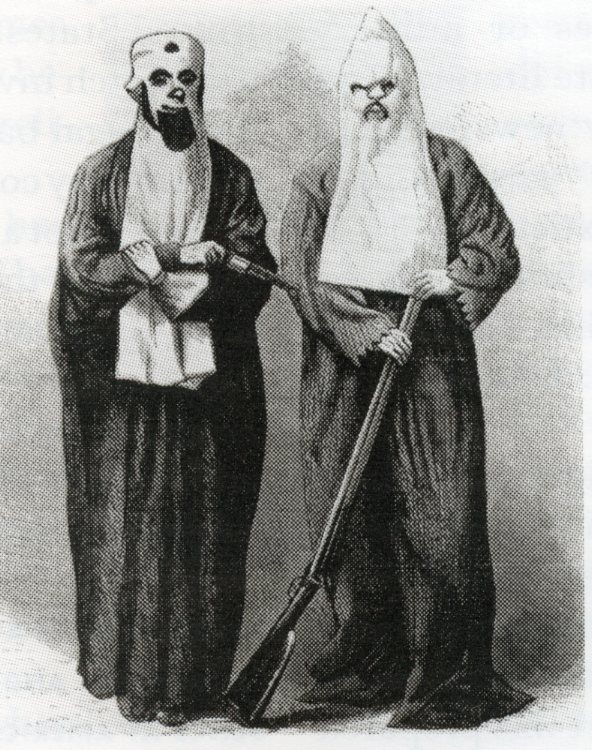

Soon after the founders named the Klan, they decided to do a bit of showing off, and so disguised themselves in sheets and galloped their horses through the quiet streets of tiny Pulaski. their ride created such a stir that the men decided to adopt the sheets as the official regalia of the Ku Klux Klan, and they added to the effect by donning grotesque masks and tall pointed hats. They also performed elaborate initiation ceremonies for new members. Similar to the hazing popular in college fraternities, the ceremony consisted of blindfolding the candidate, subjecting him to a series of silly oaths and rough handling, and finally bringing him before a “royal altar” where he was to be invested with a “royal crown.” the altar turned out to be a mirror and the crown two large donkey’s ears. Ridiculous though it sounds today, that was the high point of the earliest activities of the Ku Klux Klan.

Had that been all there was to the Ku Klux Klan, it probably would have disappeared as quietly as it was born. But at some point in early 1866, the club added new members from nearby towns and began to have a chilling effect on local blacks. The intimidating night rides were soon the centerpiece of the hooded order: bands of white-sheeted ghouls paid late night visits to black homes, admonishing the terrified occupants to behave themselves and threatening more visits if they didn’t. It didn’t take long for the threats to be converted into violence against blacks who insisted on exercising their new rights and freedom. Before its six founders realized what had happened, the Ku Klux Klan had become something they may not have originally intended — something deadly serious.

The scholar Gladys-Marie Fry, who writes about slave patrols in her book, Night Riders in Black Folk History (University of Tennessee Press, 1977), believes it was no accident that the early Klansmen chose white sheets for their costumes. The following story was told to her by a black resident of Washington, D.C., who heard the story from his ex- slave ancestors:

“Back in those days they had little log cabins built around in a circle, around for the slaves. And the log cabins, they dabbed between two logs, they dabbed it with some mortar. And of course when that falls out, you could look out and see. But every, most every night along about eight or nine o’clock, this overseer would get on his white horse and put a sheet over him, and put tin cans to a rope and drag it around. And they told all the slaves, ‘now if you poke your head out doors after a certain time, monster of a ghost will get you.’ they peeped through and see that and never go out. They didn’t have to have any guards.”

Fry said such disguises meant to scare slaves were common and that the first Klansmen, knowing this, naturally chose similar uniforms, often embellishing them with fake horns and paint around the lips and eyes.

Relying heavily on the oral testimony of contemporary blacks whose parents or grandparents were slaves, Fry concludes that many slaves were superstitious, with real fears of ghosts, “haints,” and the supernatural. But she said most slaves knew when white slave owners and patrollers were trying to fool them. One ex-slave told a Federal writer’s project interviewer during the 1930s, “Ha! ha! dey jest talked ‘bout ghosts till I could hardly sleep at night, but the biggest thing in ghosts is somebody ‘guised up tryin’ to skeer you. ain’t no sich thing as ghosts.” another former slave reported, “Dey ghost dere — we seed ‘em. Dey’s w’ite people wid a sheet on ‘em to scare de slaves offen de plantation.”

According to Fry’s research, slaves may have been frightened by the slave patrols, but they were far from defenseless. A common trick of the patrollers was to dress in black except for white boots and a white hat, which did make a ghostly sight when a group of them were riding along on a dark night. On one such occasion, however, slaves stretched grapevines across the road at just the right height to strike a rider on horseback. The slave patrol came galloping along and hit the grapevines; three patrollers were killed and several others injured. There were no more mounted slave patrols for a long time afterwards in that county.

After the Civil war, when the Ku Klux Klan served the same purpose of controlling blacks as the slave patrols had, many whites (and later historians) mistook the surface behavior of blacks for their genuine feelings. For blacks, Fry says, “appearing to believe what whites wanted them to believe was a part of wearing the mask and playing the game . in another instance, on ex-slave who heard rumors of strange riders in his neighborhood went to his former master for information. The master told him, ‘there are Ku Klux here; are you afraid they will get among you?’ the black said, ‘what sort of men are they?’ the reply: ‘they are men who rise from the dead.’ according to the Congressional committee’s report, this informant gave the matter considerable thought and rejected it. In his own words: ‘I studied about it, but I did not believe it.’ “

Fry continues, “It is significant that the early Klan made such great efforts to frighten and terrorize blacks through supernatural means. The whole rationale for psychological control based on a fear of the supernatural was that whites were sure that they knew black people. they were not only firmly convinced that black people were gullible and would literally believe anything, but they were equally sure that blacks were an extremely superstitious people who had a fantastic belief in the supernatural interwoven into their life, folklore, and religion.

“Such thinking had obvious flaws: the underestimation of black intelligence and the overvaluation of existing superstitious beliefs. Blacks were frightened, no doubt, but not of ghosts. They were terrified of living, well-armed men who were extremely capable of making black people ghosts before their time.”

Few eras of United States history are as entangled in myth and legend as the period of 1865 to 1877, known as the reconstruction. For the modern Klansman, this period of history is vitally important, and the retelling of the events of those days is a basic element of Klan propaganda.

The Klan version of reconstruction goes like this: in the dark days immediately after the Civil war, Southerners were just beginning to pick up the pieces of their shattered lives when an evil and profit-minded coalition of northern radical republicans, carpetbaggers and Southern scalawags threw out legitimate Southern governments at bayonet point and began installing illiterate blacks in state offices. Worse, the conspirators aroused mobs of savage blacks to attack defenseless whites while the South was helpless to do anything about it. The radicals pulling the strings behind the scenes stole Southern state governments blind and sent them deeply into debt. After a few years of this, the Ku Klux Klan arose, drove out the carpetbaggers and radicals and restored white Southerners to their rightful place in their own land.

Like all legends and myths, this particular scenario starts out with a few grains of truth, but winds up being a romanticized story; a version of history that white Southerners in the late 1800s wanted very badly to believe was true.

No events of this period illustrate the inaccuracy of the legend better than the race riots which occurred in Memphis and New Orleans in the first half of 1866. In both cases, white city police attacked groups of blacks without provocation and killed scores of men, women and children with the help of armed white mobs behind them. These were the worst incidents of white organized violence against blacks in that year, but by no means the only ones.

The next phase of the story concerns the reconstruction governments that were installed in 1867 after Congress abolished the renegade governments formed by the ex-Confederate states immediately after the war. Some of these newly formed governments were indeed corrupt and incompetent, as white supremacists maintain. But historians who have studied these governments have found that often the greatest beneficiaries of the corruption were aristocratic white Southerners.

One historian summed up the radical governments this way: “Granting all their mistakes, the radical governments were by far the most democratic the South had ever known. They were the only governments in Southern history to extend to Negroes complete civil and political equality, and to try to protect them in the enjoyment of the rights they were granted.” and when these governments were replaced by all-white conservative governments, most of these rights were stripped away from blacks and in some cases from poor whites as well.

The restoration of white government in the South was called “redemption,” and although there are many historical reasons for the change, it was a development for which the Klan claimed credit, thereby placing the secret society in what it viewed as a heroic role in Southern history.

William J. Simmons, a Spanish war veteran-turned preacher-turned salesman, was a compulsive joiner who held memberships in a dozen different societies and two churches. But he had always dreamed of starting his own fraternal group, and in the fall of 1915 he put his plans into action.

On Thanksgiving eve, Simmons herded 15 fellow fraternalists onto a hired bus and drove them from Atlanta to nearby Stone Mountain. There, before a cross of pine boards, Simmons lit a match, and the Ku Klux Klan of the 20th century was born.

Although Simmons adopted the titles and regalia of the original version, his new creation at its outset had little similarity to the Reconstruction Klan. It was, in fact, little different from any of the dozens of other benevolent societies then popular in America. There is little doubt that Simmons’ ultimate purpose in forming the group was to make money. But growth at first was slow, even after America entered World War I in 1917 and the Klan had a real “purpose” — that of defending the country from aliens, idlers and union leaders.

Then, in 1920 Simmons met Edward Young Clarke and Elizabeth Tyler, two publicists who had formed a business in Atlanta. In June 1920, with the Klan’s membership at only a few thousand, Simmons signed a contract with Clarke and Mrs. Tyler giving them 80 percent of the profits from the dues of the new members Simmons so eagerly sought. The new promoters used an aggressive new sales pitch — the Klan would be rabidly pro American, which to them meant rabidly anti-black, anti-Jewish, and most importantly, anti-Catholic.

Simmons graphically illustrated the new approach when he was introduced to an audience of Georgia Klansmen and drew a Colt automatic pistol, a revolver and a cartridge belt from his coat and arranged them on the table before him. Plunging a Bowie knife into the table beside the guns, he issued an invitation: “Now let the Niggers, Catholics, Jews and all others who disdain my imperial wizardry, come out!”

The message was clear — the new Klan was serious. That meant expanding its list of enemies to include Asians, immigrants, bootleggers, dope, graft, night clubs and road houses, violation of the Sabbath, sex, pre- and extra-marital escapades and scandalous behavior. The Klan, with its new mission of social vigilance, soon had organizers scouring the nation, probing for the fears of the communities they hit and then exploiting them to the hilt.

And the tactic was immediately a raging success. By the late summer of 1921, nearly 100,000 had enrolled in the Invisible Empire, and at $10 a head (tax-free since the Klan was a “benevolent” society), the profits were impressive. While Simmons made speeches and tinkered with ritual, Clarke busied himself with expanding the treasury, launching Klan publishing and manufacturing firms and investing in real estate. The future looked very good.

But during that summer the Klan leaders in Atlanta ran into their first trouble — controlling their far-flung empire. While Klan officials talked of fraternal ideals in Atlanta, their members across the nation began to take seriously the fiery rhetoric the recruiters were using to drum up new initiation fees. Violence first flared in a rampage of whippings, tar-and-feathers raids and the use of acid to brand the letters “KKK” on the foreheads of blacks, Jews and others they considered anti-American. Ministers, sheriffs, policemen, mayors and judges either ignored the violence or secretly participated. Few Klansmen were arrested, much less convicted.

In September 1921 the New York World began a series of articles on the Klan, backed up by the revelations of an ex-recruiter. Another newspaper reported some of the internal gossip and financial manipulations within the Atlanta headquarters. And even more embarrassing was a story in the World that Clarke and Mrs. Tyler had been arrested, not quite fully clothed, in a police raid on a bawdy house in 1919.

The article badly tarnished the Klan’s moralistic image and precipitated a serious rift within the ranks. The World exposés also brought demands for countermeasures, and congress responded in October 1921 with hearings into the Klan’s activities. Although the congressional inquiry so upset Clarke that he considered resigning, the actual hearings did little damage to the Klan. Simmons explained away the secrecy of the Klan as just part of the fraternal aspect of the organization. He disavowed any link between his Klan and the nightriders of reconstruction days, and he denied — just as Forrest had done 50 years earlier — any knowledge of or responsibility for the violence. The committee adjourned without action, and the Klan benefited from all the publicity.

It almost seemed as if people in the rural areas of the country were determined to support whatever the big newspapers and congress condemned. Following more articles in the World in October (these concentrating on the violent nature of the Klan), membership in the Invisible empire exploded. “It wasn’t until the newspapers began to attack the Klan that it really grew,” Simmons recalled later. “Certain newspapers also aided us by inducing congress to investigate us. The result was that congress gave us the best advertising we ever got. Congress made us.”

With the Klan’s new strength came prolonged internal bickering. In the fall of 1922, with Texas dentist Hiram Wesley Evans leading the way, six conspirators made plans to dethrone Simmons. Evans became imperial wizard, and in 1923 the conspirators saw a chance to grab permanent control of the Klan’s property, worth millions by this time. When Clarke was indicted on a two-year-old morals charge, Evans was able to cancel the promoter’s lucrative contract with the Klan and thus seize control of the money-making dues apparatus. Mrs. Tyler had already resigned to get married, so that left only Simmons, who became furious when he realized he had been out-maneuvered by Evans and his faction.

A full-scale war was fought between the Evans and Simmons factions with lawsuits and countersuits, warrants and injunctions, all gleefully reported in newspapers across the country. The fight spilled over into chapters in Texas and Pennsylvania and resulted in the shooting of Simmons’ lawyer by Evans’ chief publicity man. The power struggle ended in February 1924, when Simmons agreed to a cash settlement.

The Klan continued to grow during this period of internal strife, but its weaknesses were laid open for America to see. The Klan promoted itself as an organization dedicated to defending the morals of the nation, but there had been too many charges of immorality against its leaders. It’s supposed nonprofit status was badly undermined by the wrangling over finances, and most of its vaunted secrecy was exposed in the reams of court documents churned out by the feuding.

And its violence was clearly revealed. Under Evans, the Klan launched a campaign of terrorism in the early and mid-1920S, and many communities found themselves firmly in the grasp of the organization. Lynching’s, shootings and whippings were the methods employed by the Klan. Blacks, Jews, Catholics, Mexicans and various immigrants were usually the victims.

But not infrequently, the Klan’s targets were whites, Protestants and females who were considered “immoral” or “traitors” to their race or gender. In Alabama, for example, a divorcee with two children was flogged for the “crime” of remarrying and then given a jar of Vaseline for her wounds. In Georgia, a woman was given 60 lashes for a vague charge of “immorality and failure to go to church”; when her 15-year-old son ran to her rescue, he received the same treatment. In both cases, ministers led the Klansmen responsible for the violence.

But such instances were not confined to the South. In Oklahoma, Klansmen applied the lash to girls caught riding in automobiles with young men, and very early in the Klan revival, women were flogged and even tortured in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

In a period when many women were fighting for the vote, for a place in the job market and for personal and cultural freedom, the Klan claimed to stand for “pure womanhood” and frequently attacked women who sought independence.

During the period of its most uncontrolled violence, the Klan also experienced unprecedented political gains. In 1922, Texas sent Klansman Earl Mayfield to the U.S. Senate, and Klan campaigns helped defeat two Jewish congressmen who had headed the Klan inquiry. Klan efforts were credited with helping to elect governors in 12 states in the early 1920s.

With two million members, new recruits joining the secret rolls daily, a host of friendly politicians throughout the land and his internal enemies subdued for the moment, Evans wanted to influence the presidential election of 1924. He even shifted his national headquarters from Atlanta to Washington. The Klan had a foothold in both parties since Deep South members tended to be Democrats while Klansmen in the North and West were often Republicans. But of the three major Presidential candidates, two were outspoken enemies of the Ku Klux Klan. And when the Democratic convention opened in New York, many Democrats were demanding the party adopt a platform plank condemning the Ku Klux Klan. The resulting fight tore the convention apart. After days of bitter wrangling over the issue, the platform plank denouncing the Klan lost by a single vote.

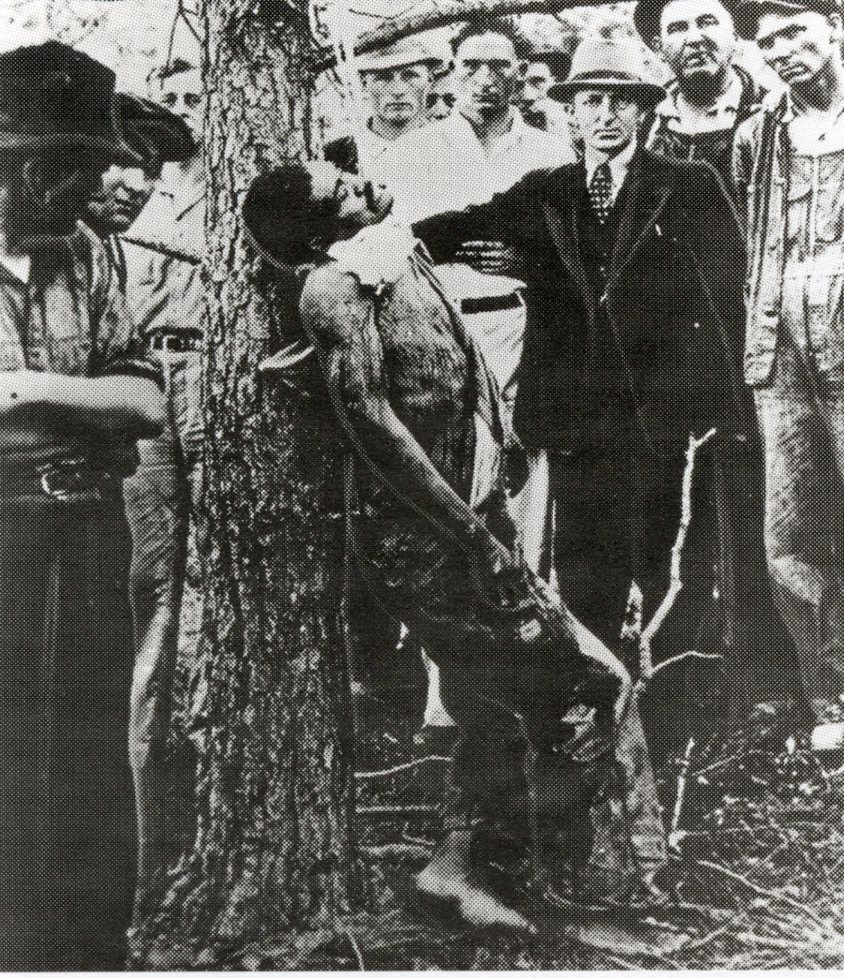

Although politicians became increasingly uncomfortable with Klan allies as a result of the turmoil, the success of the Klan candidates across the nation in 1924 buoyed Evans’ spirits. His notoriety peaked with a parade of 40,000 Klansmen down Washington’s Pennsylvania Avenue to the Washington Monument in August 1925. Evans boasted of having helped reelect Coolidge, of having secured passage of strict anti-immigration laws and of having checked the ambitions of Catholics and others intent on “perverting” the nation. The Klan was riding high.

But the decline of the Ku Klux Klan was already well underway. By 1926, when Evans tried to repeat the parade in Washington, only half as many marchers arrived, and they were sobered by the news of political defeats in areas that a year before had been considered safe Klan strongholds.

Increasingly the Klan suffered counter attacks by the clergy, the press and a growing number of politicians. Then, in 1927, a group of rebellious Klansmen in Pennsylvania broke away from the Invisible Empire, and Evans promptly filed a $100,000 damage suit against them, confident that he could make an example of the rebels. To his surprise, the Pennsylvania Klansmen fought back in the courts, and the resulting string of witnesses told of Klan horrors, terrorism and violence, named members and spilled secrets. Newspapers carried accounts of testimony ranging from the kidnapping of a small girl from her grandparents in Pittsburgh to a Colorado Klansman who was beaten when he tried to quit. One particularly horrible story described how a man in Terrell, Texas, had been soaked in oil and burned to death before several hundred Klansmen. The enraged judge threw Evans’ case out of court.

The next year the Democrats nominated Al Smith — a New York Catholic and longtime Klan foe — for president against the Republicans’ Herbert Hoover. The Ku Klux Klan had a perfect issue which Evans hoped to use to whip up the faithful. But his Invisible Empire had melted from three million in 1925 to no more than several hundred thousand, and the Klan was no factor in Hoover’s election. Americans had clearly tired of the divisive effect of the masks, robes and burning crosses. What was left of the Klan’s clout disappeared as its old friends in office, smelling the new political winds, deserted the organization in droves.

During the 1930s, the nation struggled through the Great Depression, and the Klan continued to shrink. It became primarily a fraternal society, its leaders urging its members to stay out of trouble and the national headquarters hoarding its meager funds. After Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, the Klan began to charge that he was bringing too many Catholics and Jews into the government. Later they added the charge that the New Deal was tinged with communism. The red menace was used more and more by Evans and other Klansmen as the rallying cry, and communists eventually replaced Catholics as one of the Klan’s foremost enemies.

Only in Florida was the Klan still a factor in the 1930s. With a membership of about 30,000, the Klan was active in Jacksonville, Miami, and the citrus belt from Orlando to Tampa. In the orange groves of central Florida, Klansmen still operated in the old night riding style, intimidating blacks who tried to vote, “punishing” marital infidelity and clashing with union organizers. Florida responded with laws to unmask the nightriders, and a crusading journalist named Stetson Kennedy infiltrated and then exposed the Klan, rousing the anger of ministers, editors, politicians and plain citizens.

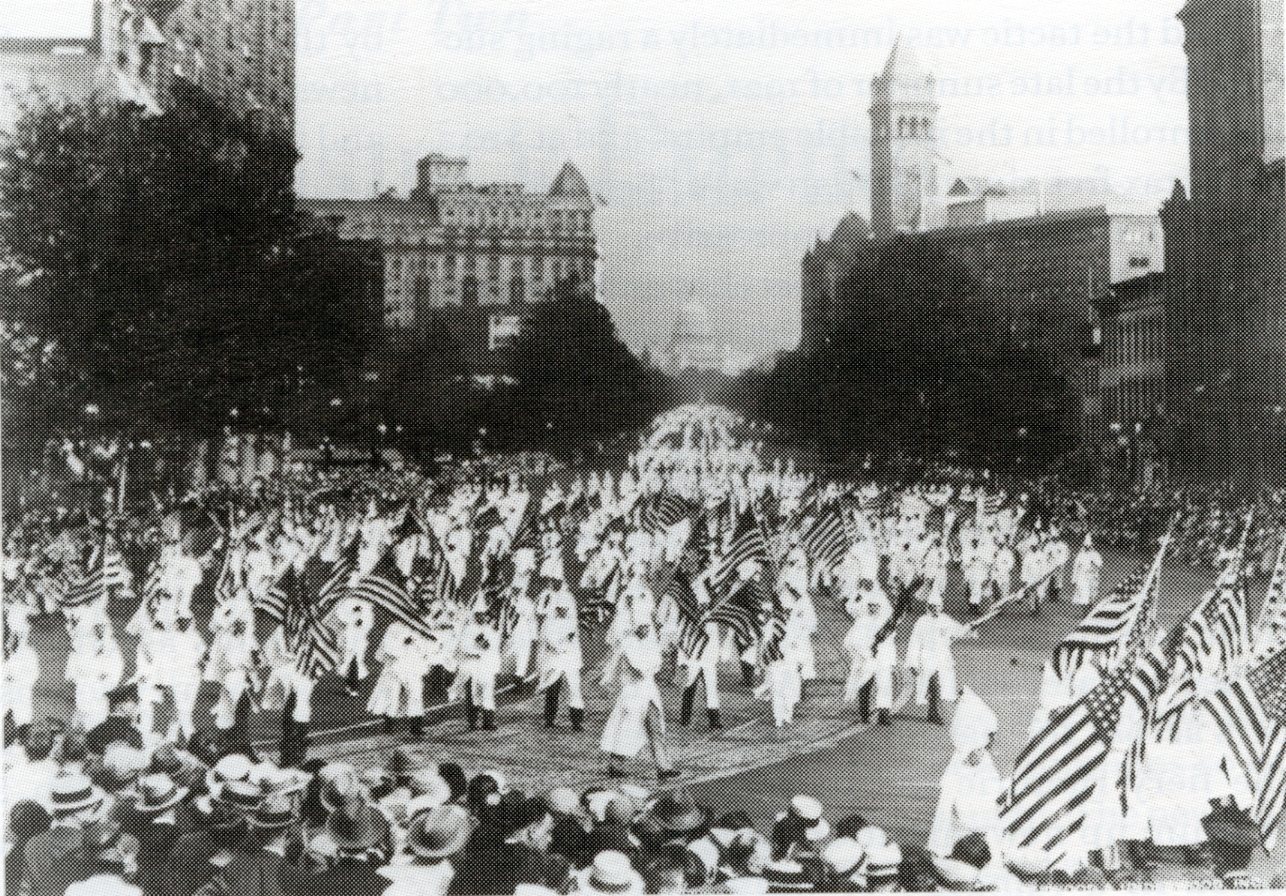

Women’s auxiliaries of the Ku Klux Klan formed their own marching corps and joined in mass Klan demonstrations.

Evans was replaced in 1939 by James A. Colescott of Indiana. He led the Klan in the Carolinas, where unions were trying to organize textile workers, and in Georgia, where nightriders flogged some 50 people during a two-year period. An outcry from the citizens of Georgia and South Carolina brought arrests and convictions, and the Klan was forced to retreat.

In the North the Klan suffered another reversal when some local Klan chapters began to develop ties with American Nazis, a move Southern Klansmen opposed but were basically powerless to stop. The end came in 1944 when the Internal revenue Service filed a lien against the Ku Klux Klan for back taxes of more than $685,000 on profits earned during the 1920s. “We had to sell our assets and hand over the proceeds to the government and go out of business,” Colescott recalled when it was over. “Maybe the government can make something out of the Klan — I never could.”

Powerful social forces were at work in the United States following World War II. A new wave of immigrants, particularly Jewish refugees, arrived from war-torn Europe. A generation of young black soldiers returned home after having been a part of a great army fighting for world freedom. In the South, particularly, labor unions began extensive campaigns to organize poorly paid workers. The migration from the farms to the cities continued, with a resulting shakeup in old political alliances.

Bigots began to howl more loudly than in years, and a new Klan leader began to beat the drums of anti-black, anti-union, anti-Jew, anti-Catholic and anti-communist hatred. This man was Samuel Green, an Atlanta doctor. Green managed to reorganize the Klan in California, Kentucky, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee, Florida and Alabama. But both federal and state bureaus of investigation prosecuted Klan lawlessness, and Green found that his hooded order was surrounded by enemies. The press throughout the South had become increasingly hostile; ministers were more and more inclined to attack the Klan, and state and local governments passed laws against cross burnings and masks.

By the time of Green’s death in August 1949, the Klan was fractured internally by disputes and hounded by investigations from all sides in response to a wave of Klan violence in the South. Many Klansmen went to jail for floggings or other criminal acts. By the early 1950s, the Invisible Empire was at its lowest level since its rebirth on Stone Mountain in 1915.

Groups like the Klan can move into a community overnight. it isn’t always the number of Klansmen involved that causes the most trouble, but the tactics they use and the response they meet. History warns against taking the Klan lightly, as demonstrated by events in Oregon in the 1920s.

Oregon in the spring of 1921 was as unlikely a potential Ku Klux Klan stronghold as any state in the nation. It was peaceful and quiet, its fine school system had virtually banished illiteracy, and no one was making fiery speeches about race (97 percent of the people were white) or immigrants (87 percent were native born).

Incredibly, within a year of the arrival of a single Klan salesman, Oregon was so firmly in the grasp of the hooded nightriders that the governor admitted they controlled the state. Just as amazing, by 1925 the people of Oregon had thrown off the Klan’s shackles of hate and fear and the hooded order faded.

The Oregon chapter began when the Klan salesman, Luther Powell, arrived from California looking for new recruits. He sized up the state of affairs in Oregon and decided he would make the lax enforcement of prohibition his first issue. Anti-Catholicism would later prove more productive, but for Powell’s first organizational meeting the prohibition issue was good for 100 new Klansmen, including lots of policemen. Then his new Klan lynched a black who had been convicted of bootlegging.

Next, Klansmen ordered a salesman and a black man they disliked to leave the state. Crosses were burned on the hillsides around several towns, and an “escaped nun” was brought into the area to tell made-up horrors about the Catholic clergy. This was followed by the distribution of hate pamphlets in some churches to whip up the fears and suspicions of the people.

With this pattern established, the Klan began to spread. Its tactics included boycotts, recall campaigns against unfriendly officeholders, infiltration and takeover of churches, and division of every community it touched into two bitterly antagonistic camps. Politicians, ministers, newspaper editors and other civic leaders throughout the state said and did nothing. Within a year, Oregon’s governor, Ben Olcott, told fellow governors at a meeting: “We woke up one morning and found the Klan had gained political control of our state. Practically not a word had been raised against them.”

And in fact, a later study showed that at least as far as the press was concerned, Gov. Olcott was almost literally correct — hardly a word was raised against the spread of Klan intimidation. Despite what was happening all around them, Oregon’s newspapers remained silent on the subject of the Ku Klux Klan, even to the extent of not printing news of national Klan events then making headlines across the country. Citizens of Oregon who relied on their newspapers to tell them what was happening in their communities would never have known the Klan seized control.

Thus, few people realized how few citizens actually belonged to the Klan in Oregon. When the governor admitted the Klan takeover, the hooded order had only about 14,000 members — about two percent of the state’s population. The next year, the Klan’s high-water mark was reached — 25,000 members.

The Klan’s grand dragon in Oregon during its period of ascendancy was a railroad worker named Fred Gifford. He took over after the national organization’s representatives in the state squabbled over initiation fees. He sought to dominate the entire state, helped in part by the utility companies, to which he was strongly tied.

The Ku Klux Klan’s reign in Oregon turned out to be very short, however. Hungry for more power, Gifford began to make enemies within his own organization and throughout the state. A newspaper in Salem finally began printing hostile stories, exposing Klan activities and corrupt practices. Other papers followed suit and a number of ministers began attacking the Klan from their pulpits. By 1926, Gifford’s power had so waned that in an effort to help a candidate for office, he publicly supported the man’s opponent.

The rapid rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon illustrates what can happen to a community when its citizens pretend not to see or hear the hatred around them. There were many reasons for the rapid Klan triumph, but the silence of the state’s leaders as the shadow spread over them was certainly a major factor. And the Klan’s fall, although it too had many causes, was largely the product of the courage of the state’s governor, its clergy, its newspapers and civic leaders who finally spoke out against the Klansmen.

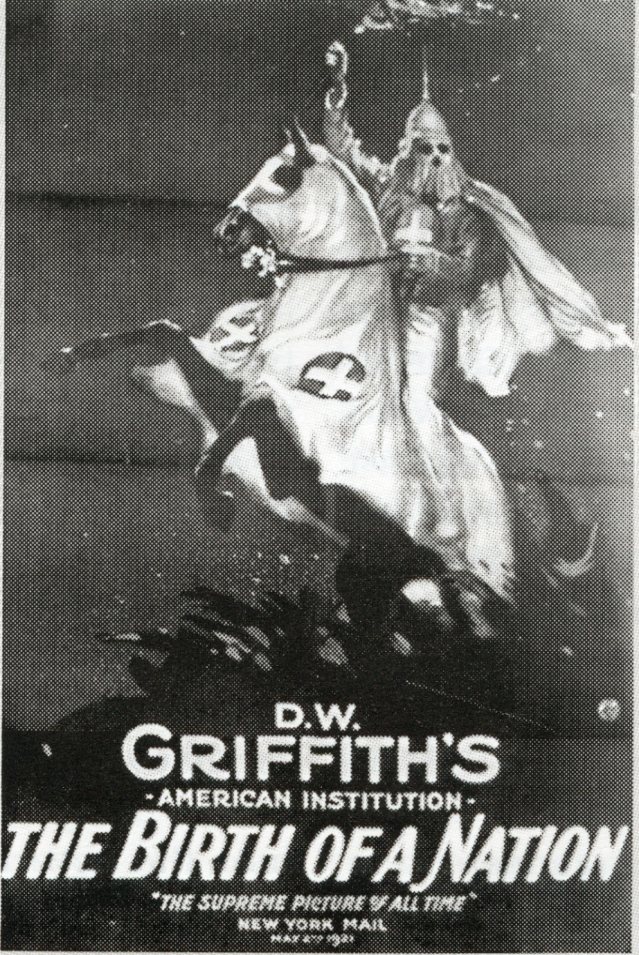

Sooner or later just about every Klansman worthy of his robe sees the silent film classic Birth of a Nation, which is usually accompanied by a stirring narrative of the two hour and 45 minute saga. For those who believe in the legend of the Ku Klux Klan as the savior of the South during reconstruction, the movie has always been one of the most powerful pieces of propaganda in the Klan’s arsenal.

Released in 1915, Birth of a Nation was a cinematic masterpiece that set new standards for the fledgling film industry. The story it tells fits perfectly into the version of history the Klan preaches. The movie, based on a novel by North Carolina minister Thomas Dixon Jr., was the brainchild of a talented young director, D.W. Griffith. In an era of short, slapstick nickelodeon comedies, Griffith wanted to film a masterpiece that would tell the grand story of events leading up to the Civil war, the great conflict itself, and finally the tragedy and suffering of reconstruction, complete with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

In making his epic, Griffith blended the almost magical appeal of the pre-war South, the heroics of the great Civil war battles and all the stereotypes and myths of reconstruction with a skill that made the picture a sensation. The plot is a cotton-candy love story between a Southern colonel and the prison nurse who tended to him. The cast includes an evil northern congressman, who wanted the South to be punished for the war; a brutish carpetbagger; loyal black family servants; a sex-crazed black rapist, and loutish, power-mad black reconstruction legislators and soldiers.

The suspense builds until finally the demure sister of Ben Cameron, the Southern colonel, leaps to her death to avoid being raped by a lecherous black. With this outrage, the Ku Klux Klan enters the picture, riding the South Carolina piedmont to rid the land of the scourge that had descended upon it. To audiences accustomed to nothing more than one-reel comedies and melodramas, the panoramic epic was a blockbuster.

The son of an ex-Confederate officer, Griffith viewed his material as nothing less than history on the screen, but the first showings of the movie provoked a storm of indignant protest in northern cities. Thomas Dixon, the novel’s author, effectively smoothed the way for widespread acceptance of the picture by cleverly arranging for a screening for his old classmate, President Woodrow Wilson, and the Cabinet and their families. Wilson emerged from the showing very moved by the film and called it “like writing history with lightning . my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”

The movie went on to gross $18 million before it was retired to art theaters and film clubs. So powerful was the impact of the movie in 1915 that it is often credited with setting the stage for the Klan revival that same year. In fact, the man who actually created the 20th century Klan, William J. Simmons, was acutely aware of the promotional value of the film, and he used the publicity surrounding it to win recruits to his organization. Modern Klan leaders still use the movie as a recruiting gimmick and provide their own narration to the silent film.

Although the film is still regarded by critics as an early masterpiece for its direction and inventive uses of the camera, Birth of a Nation is so blatantly racist that it is rarely shown in public theaters today. Protest demonstrations frequently disrupt scheduled screenings. Now, only the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists still claim any historical authenticity for the movie.

The Klan’s use of the film is a good indication of how out-of-touch white supremacists are with the predominant American attitudes on race. The racial hatred exhibited in the movie, once acceptable, is now abhorrent to all but the Klan and the most extreme bigots.

The study of the ebb and flow of the Ku Klux Klan in the United States reveals a pattern: the Klan is strong when its leaders are able to capitalize on social tensions and the fears of white people; as its popularity escalates and its fanaticism leads to violence, there is greater scrutiny by law enforcement, the press and government; the Klan loses whatever public acceptance it had; and disputes within the ranks finally destroy its effectiveness as a terrorist organization.

The Civil Rights Era Klan conforms to the pattern. When the Supreme Court threw out the “separate but equal” creed and ordered school integration in 1954, many whites throughout the South were determined to oppose the law and maintain segregation. Like the Southern opposition to Reconstruction government, the tensions and fears that arose after the Supreme Court decision provided the groundwork for Klan resurgence.

In 1953, automobile plant worker Eldon Edwards formed the U.S. Klan’s, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, in Atlanta, but he attracted few members until the Supreme Court decision the following year. By September 1956, Edwards was host to one of the largest Klan rallies in years, drawing 3,000 members to Stone Mountain, the site of the rebirth of the Klan in 1915. By 1958, Edwards’ group had an estimated 12,000 to 15,000 members.

The U.S. Klan’s wasn’t the only Klan organization trying to gain a stronghold in the South; a number of rival factions made a name for themselves through gruesome acts of violence. A U.S. Klan’s splinter group in Alabama was responsible for the 1957 assault on Edward “Judge” Aaron, a black handyman from Birmingham. Members abducted him, castrated him and poured hot turpentine into his wounds.

Edwards died in 1960, and the U.S. Klan’s organization fell into disarray. The next year, Robert M. Shelton, an Alabama salesman, formed the United Klan’s of America. Shelton achieved national notoriety when his Klansmen viciously beat black and white freedom riders in Birmingham, Montgomery and Anniston and joined in violent confrontations on university campuses in Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi.

By 1964 Shelton had a loosely organized Klan empire throughout the South. By 1965, total Klan membership had reached an estimated 35,000 to 50,000.

The South in the early 1960s was the site of daily tensions between those who favored integration and those who opposed it, and the tensions sometimes led to bloodshed. Civil rights marchers were attacked in Birmingham by police with dogs and fire hoses. Freedom riders — blacks and whites who rode buses throughout the South to protest racial inequities — were mobbed by Klansmen in planned attacks. Civil rights leaders had their homes burned and their churches bombed.

Klan members were involved in much of the racial violence that spread throughout the South, and the fanatic Klan rhetoric inspired non-Klan members to participate in the campaign of terror. No Klan group was more ruthless than the secretive White Knights of Mississippi. The White Knights had only 6,000 or 7,000 members at its peak, but still earned the reputation as the most bloodthirsty faction of the Klan since reconstruction. The White Knights committed many crimes during the 1960s, but the most shocking were the murders of one black and two white civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi, on June 21, 1964.

There were other senseless Klan killings during the 1960s. Among the victims were: Lt. Col. Lemuel Penn, a black educator who was shot as he was returning to his home in Washington after summer military duty at ft. Benning, Georgia; rev. James Reeb, who was beaten during voting rights protests in Selma, Alabama; and Viola Liuzzo, a civil rights worker who was shot in 1965 while driving between Montgomery and Selma.

Klansmen discovered dynamite as a weapon of terror and destruction. The use of bombs by Klansmen dated back to January 1956, when the home of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery was blasted. Between that incident and June 1, 1963, some 138 bombings were reported, and the Klan was believed responsible for many of them.

One bombing stands out in the history of the Klan and its fanatical fight against integration in the South. On Sept. 15, 1963, a dynamite bomb ripped apart the 16th Street Baptist church in Birmingham, killing four young black girls. Of all the crimes committed by all the desperate men under the sway of the Klan’s twisted preaching, the Birmingham church bombing remains in a category by itself.

All told, the Klan’s campaign of terror against the civil rights Movement resulted in almost 70 bombings in Georgia and Alabama, the arson of 30 black churches in Mississippi, and 10 racial killings in Alabama alone.

Klansmen were often operating in an atmosphere of official disapproval but unofficial acceptance of their tactics. While Southern law enforcement authorities made perfunctory efforts to arrest and prosecute the bombers, politicians pledged resistance to integration, and communities responded by closing ranks against blacks.

The acts of violence finally began to arouse public indignation in the South and across the nation. In 1964, a silent counterattack was begun by the FBI, which made a major effort to infiltrate the Klan. By September 1965, the FBI had informants at the top level of seven of the 14 different Klan’s then in existence. Of the estimated 10,000 active Klan members, some 2,000 were relaying information to the government. Although the FBI arrested Klansmen and prevented some violence because of this information, critics accuse the Bureau of improperly controlling some informers who may have been involved in illegal acts themselves.

In 1965, Klan violence prompted President Lyndon Johnson and Georgia congressman Charles L. Weltner to call for a congressional probe of the Ku Klux Klan. The resulting investigation produced a parade of tight-lipped Klansmen, evasive answers and tales of violence as had similar probes in 1871 and 1821.

This time, however, the House of Representatives voted to cite seven Klan leaders, including Shelton, for contempt of congress for refusing to turn over Klan records. The seven Klansmen were indicted by a federal grand jury and found guilty in a Washington trial. Shelton and two other Klan leaders spent a year in prison.

FBI pressure, the congressional probe and Southerners’ weariness of violence took its toll on the Klan. Shelton and other Klan leaders still raged at blacks, Jews and other imagined enemies of the nation, but increasingly their public activities were confined to rallies and speeches while they privately tried to hold together their fractured empires. Some of their members drifted away, some were convicted like Shelton and sent to prison, and some remained active but seemed less eager for clashing with authorities.

The stalwarts of the Klan kept hammering away at the old themes of hatred. Though calls for violence were now muted, their fanaticism was undimmed. Instinctively, they seemed to know their fight would carry on into the 1970s and beyond, fueled by the vulnerability of some Americans to the cry of racial prejudice that brought the Klan to life three times in the century following the Civil War.

The civil rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, was built by the Southern Poverty Law center as a perpetual reminder of the sacrifices that were made to end racial segregation in the South. The names of 40 individuals, killed because they stood up for human rights, are inscribed in the circular black granite table that serves as the centerpiece of the Memorial. These are the true heroes of the civil rights Movement — their martyrdom made freedom possible for millions in the South.

For every story of courage that is represented on the Memorial, there is a parallel one of evil and violence. For every person killed, there was a killer — in most cases more than one. Some acted out of impulsive rage. Others used their legal authority to enforce the rules of a dying social order.

In many cases, the killer was never apprehended, the crime concealed by a code of silence.

At the forefront of the racial terrorism of the 1950s and 1960s was the Ku Klux Klan. Klansmen have been identified as the killers of 14 of the individuals honored on the Memorial. Their stories are told below. But that number is surely an incomplete accounting. Many killings attributed to unknown night riders were likely the work of the Klan.

The deaths remembered on the civil rights Memorial offer undisputed testimony to the Klan’s willingness to use murder as a tool to enforce its belief in white supremacy. The heroic spirit of those who gave up their lives in the cause of racial freedom should not be forgotten. Nor should the crimes of those who forced them to make that sacrifice.

23 • January • 1957

WILLIE EDWARDS JR.

KILLED BY KLAN

MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA

The racial climate in Montgomery, Alabama, was palpably ugly in early 1957. A grass-roots movement of black citizens — led by the rev. Martin Luther King Jr. — had recently forced the integration of the city transit system. The Ku Klux Klan reacted violently. Members of the Klan marched through Montgomery in an effort to terrorize black bus riders and bombed the homes and businesses of boycott supporters.

Several members of a local Ku Klux Klan group decided that only the murder of a black would express their outrage. Willie Edwards Jr., a quiet man who had kept his distance from the bus boycott, became the unfortunate victim of their deadly resolve.

On Jan. 23, Edwards was substituting for the driver of a supermarket delivery truck when the Klansmen pulled him over on a rural stretch of road outside Montgomery. Their intent was to harass the regular driver of the truck, whom they suspected of dating a white woman. Not knowing what he looked like, they mistakenly assumed that Edwards, the fill-in, was their target.

The Klansmen forced Edwards into their vehicle and drove through rural Montgomery County. Though Edwards denied making advances to white women, his kidnappers tortured him repeatedly. Finally, they ordered him at gunpoint to jump off a bridge over the Alabama river. Seeing his only hope of escape, he leaped into the water below. His decomposed body was found three months later.

The investigation turned up no suspects and was quickly closed. Some 19 years later, the Alabama attorney general indicted three Klansmen for edwards’ murder. But a judge threw out the indictments on a legal technicality, and the men were never brought to trial.

15 • September • 1963

ADDIE MAE COLLINS

DENISE McNAIR

CAROLE ROBERTSON

CYNTHIA WESLEY

SCHOOLGIRLS KILLED IN BOMBING

OF 16TH ST. BAPTIST CHURCH

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA

As the summer of 1963 waned, blacks in Birmingham, Alabama, had reason to celebrate. They had bravely withstood police commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor’s fire hoses and attack dogs while marching through city streets in opposition to segregation. Stung by harsh criticism of these repressive measures, local and federal officials were dismantling laws which prohibited black access to public institutions.

But the Ku Klux Klan, holding firm to its belief in white supremacy, intensified its efforts to intimidate blacks. In the early morning hours of September 15, Klan members planted a bomb at Birmingham’s prominent 16th Street Baptist church. Some eight hours later, as Sunday worship services were about to begin, an explosion ripped through the brick structure. Four young girls — Addie Mae Collins, 14, Denise McNair, 11, Carole Robertson, 14, and Cynthia Wesley, 14 — were instantly killed. The FBI identified the group of Klansmen responsible for the bombing, but inexplicably no one was charged. It wasn’t until the Alabama attorney general reopened the case 14 years later that an arrest was made. Klansman Robert Chambliss, then 73, was found guilty of first degree murder and spent the remainder of his life in prison.

HENRY HEZEKIAH DEE

CHARLES EDDIE MOORE

KILLED BY KLAN

MEADVILLE, MISSISSIPPI

The civil rights struggle in Mississippi was fought on many fronts during the summer of 1964. College students from the North descended on Mississippi in response to the call of civil rights leaders for an all-out campaign to expose the injustices of racial segregation. White opponents fought back with a bloody campaign of beatings, church burnings and murders.

The Mississippi White Knights, known as the South’s most violent Ku Klux Klan organization, led this campaign of intimidation. Their most noted victims were three civil rights workers killed near Philadelphia, Mississippi. But one month before those murders, two White Knights were implicated in the murder of a pair of young men near the southwest Mississippi town of Meadville.

Charles Eddie Moore, 20, had just been expelled from college for participating in a student demonstration. Henry Hezekiah Dee, 19, worked in a local lumber yard. Two White Knights — James ford Seale, 29, and Charles Marcus Edwards, 31 — were convinced that the two young men were part of a rumored Black Muslim uprising in the area, Edwards said later. (Their information was groundless.) They abducted the young black men, took them into a nearby forest, beat them unconscious, and dumped them into the nearby Mississippi river where they drowned. Nearly two-and-a-half months passed before their remains were found.

Edwards and Seale were arrested for the murders. Edwards, a paper mill worker, gave the FBI a signed confession, but his admission of guilt was insufficient to convict him. A justice of the peace threw out the charges without explanation, and the case was never presented to a grand jury.

This pattern of law enforcement indifference to Klan-related crimes was repeated throughout the South until federal intervention forced local officials to prosecute the perpetrators of racial violence. But that shift in attitude came too late for justice to be done for Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore. Their murderers were never punished.

JAMES CHANEY

ANDREW GOODMAN

MICHAEL SCHWERNER

CIVIL RIGHTS WORKERS ABDUCTED

& SLAIN BY KLAN

PHILADELPHIA, MISSISSIPPI

Nothing enraged Mississippi Klansmen like a Northerner helping blacks achieve racial justice in their state. And if that “outsider” was a Jew, their hatred was even more intense.

Michael Schwerner, 24, epitomized the Klan stereotype of a Yankee agitator. The outspoken, self-confident Schwerner was a social worker from New York who came to Meridian, Mississippi, to work with the congress of racial equality in early 1964. He quickly earned the enmity of local Mississippi White Knights, and soon they talked openly of killing him. His efforts to build a freedom School in Philadelphia, Mississippi, provided the opportunity.

Schwerner had developed a working relationship with James Chaney, a black native of Meridian. Chaney, 21, had convinced the members of the Mount Zion Methodist church to host the Freedom School. The church’s elders previously had been reluctant to use their building for civil rights activities out of fear that the Klan would retaliate. On Sunday, June 21, their concerns were realized: arsonists firebombed the church, reducing it to a charred rubble.

Schwerner, Chaney and Andrew Goodman, 21, a newly arrived civil rights worker from New York, were on their way from Mt. Zion to Philadelphia, Mississippi, when they were stopped by Neshoba county Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price. Price charged Chaney with speeding and arrested Goodman and Chaney on the absurd charge of burning Mt. Zion. Now the stage was set for local Klansmen to murder Schwerner and his accomplices.

Around 10 p.m., Price released the three civil rights workers and ordered them to return to Meridian. They had traveled only a short distance when Price, accompanied by two carloads of Klansmen, pulled the men over again. The Klansmen drove them to an isolated area where they were shot at point-blank range, one by one. They were buried in a nearby earthen dam.

The disappearance of the three men prompted a national cry of outrage. Blacks had been terrorized for decades in the South, but the violence against two white men finally moved the federal government to action. President Lyndon Johnson ordered the FBI to give the case top priority.

After a massive investigation, officers found the bodies of the dead men after paying an informant $30,000 for information on the murders.

Mississippi officials never brought charges against the murderers of Schwerner, chaney and Goodman. The Department of Justice accused 19 men of federal civil violations in connection with the incident. Seven were found guilty, but none received a sentence greater than 10 years.

LT. COL LEMUEL PENN

KILLED BY KLAN

COLBERT, GEORGIA

Although the U.S. Armed forces was integrated after World War II, the American South in the 1960s remained hostile to blacks — service members or not. So when Army reserve officer Lt. Col. Lemuel Penn, 49, left his home in Washington, D.C., in June 1964 to attend summer training at ft. Benning, Georgia, he timed his trip to avoid unnecessary stops.

His attempt to escape confrontation proved tragically unsuccessful. While he and two other black army officers were driving back to Washington on July 11, Penn was accosted outside of Athens, Georgia, by a carload of Klansmen and shot at point-blank range. The three assailants were members of a violent Klan group called the Black Shirts. They were searching for “out-of town niggers [who] might stir up some trouble in Athens,” the driver of the car confessed later.

An investigation implicated the Athens Klansmen in the crime. Cecil William Myers and Joseph Howard Sims were tried on first-degree murder charges, but an all-white jury acquitted them despite the driver’s confession. Later, the Department of Justice brought civil rights charges against Myers, Sims and four other Klansmen. After a lengthy proceeding, which went all the way to the U.S. Supreme court, Myers and Sims were convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison. Their accomplices were set free.

25 • March • 1965

VIOLA GREGG LIUZZO

KILLED BY KLAN

WHILE TRANSPORTING MARCHERS

SELMA HIGHWAY, ALABAMA

On the night of Sunday, March 7, 1965, Americans received a close-up view of the harsh methods employed by Southern law enforcement officers against civil rights activists. News broadcasts that evening showed Alabama state troopers brutally beating participants in a voting rights march as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. It was a critical turning point in the civil rights movement in America.

Many viewers merely expressed outrage at the incident. Viola Gregg Liuzzo, a mother of five from Michigan, was moved to action. She traveled to Selma to participate in the struggle for racial equality and soon was ferrying marchers on the road between Selma and Montgomery as the demonstrations in support of voting rights continued.

Liuzzo’s presence in Selma and the casual way she interacted with black marchers enraged a group of Klansmen who were assigned to terrorize the protesters. They chased down Liuzzo’s Oldsmobile on the highway between Selma and Montgomery, and one of the group shot her through the car window. She died instantly.